Roy Huggins is a name I have seen on TV credits all my life.

He was a novelist who started writing for television in the 1950s and went on to create shows like Maverick, 77 Sunset Strip, The Fugitive, The Rockford Files, and many more.

His 1949 murder mystery novel, Lovely Lady, Pity Me, is a noir story of an ordinary guy, John Swanney, a reporter for a national news magazine living in Los Angeles, whose marriage has broken up, although he and his wife still share the same house. On assignment and checking out a gambling joint, John meets Ann, a beautiful, mysterious woman decked out in furs, who offers him no information about her personal life while offering him everything else.

John falls hard for Ann. (Guys like John always do. Makes you wonder if he had ever read any James M. Cain or at least seen a Fritz Lang movie. Huggins read Cain. He even mentions the author in the book.) Anyway, John and Ann meet in out-of-the-way places until he discovers, while on another assignment, that she is married to a wealthy and powerful older man.

In an attempt to straighten things out with Ann, he meets her in a dark parking lot at UCLA. Later, when John returns to his house, he finds his wife has been brutally murdered.

Knowing he will be the No. 1 suspect in the case, John contacts Ann and explains that she must tell the police they were together all evening. She refuses and John, now without an alibi, is headed for the gas chamber unless he can find out who killed his wife before the cops nab him.

Huggins creates a fast-paced story with his hero avoiding the police at every turn and at times running like mad to escape them. Lovely Lady, Pity Me, is a fun read and Huggins (1914-2002) was a good storyteller. He also provides a glimpse of L.A. in the 1940s.

In 1958, Huggins used the bare bones of this story as the second episode of 77 Sunset Strip, which he also called, “Lovely Lady, Pity Me.” In the part of John, he inserted series lead character, private investigator Stuart Bailey, which makes a neat circle. In the book, John briefly contacts Bailey. The P.I. first appeared in Huggins’ novel, The Double Take from 1946.

(For more posts on books, visit Patti Abbott’s blog.)

Friday, January 20, 2017

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Don Siegel’s Riot in Cell Block 11

There may be better prison films than “Riot in Cell Block 11,” but it sure is hard to think of one. (“Birdman of Alcatraz” might edge it out for the top spot.)

One of the toughest, most realistic movies about the prison system when it hit theaters in 1954, “Riot in Cell Block 11” still stands up as a hard, fast-paced picture with an important message.

Filmed in a nearly documentary style in California’s Folsom State Prison by director Don Siegel, an action expert, this 80-minute movie is almost non-stop action, and where there is a momentary lull in the action, there is high tension.

In the film, prisoners at the breaking point due to poor conditions, overpower their guards and seize one of the blocks – or corridors – of cells.

Leading the revolt are two of the toughest actors ever in the movies: Neville Brand as the brains, and Leo Gordon as the muscle backing him up. Gordon who was in many movies and television shows, had actually served time in prison, and, from what I have read, could scare the crap out of almost anyone on any production. Brand, who was often cast as a thug in the 1940s and 1950s in films like "D.O.A.," here gets to play a tough guy with brains and a sense of justice.

The prisoners hold the guards hostage and issue a set of demands to the governor. The demands include more space in the overcrowded facility; removal of the criminally insane to a separate cell block; and separation of young offenders with light sentences from the hardened lifers.

Understanding the issues of the prisoners of Cell Block 11, the warden, played by Emile Meyer, is well aware of the problems, but can do little about them. Policy is set by state legislators and they and the governor refuse to spend any money to correct the conditions. Caught in a difficult situation, the warden must maintain order, contain the riot, and negotiate with the prisoners while dealing with a hard-nosed flunky sent by the governor, played by Frank Faylen. Faylen, here in a serious role, was a comic actor who played Dobie Gillis’ father on TV. Emile Meyer, often cast as tough ruthless characters, like the corrupt cop in “The Sweet Smell of Success” and the vice principal of the high school in “Blackboard Jungle,” gets a complex part to play here and does an excellent job.

“Riot in Cell Block 11” is not only a terrific action movie, it addresses realistic problems. And, as far as I could see, there is not a bad scene or a wasted frame of film in the entire movie.

Don Siegel did a great job on this, one of his earlier projects as a director. He later made five films with Clint Eastwood, including “Dirty Harry,” and “Escape from Alcatraz,” and he was a mentor to Eastwood in the actor’s early efforts as a director.

(For more posts on film and TV, check out Todd Mason’s blog.)

One of the toughest, most realistic movies about the prison system when it hit theaters in 1954, “Riot in Cell Block 11” still stands up as a hard, fast-paced picture with an important message.

Filmed in a nearly documentary style in California’s Folsom State Prison by director Don Siegel, an action expert, this 80-minute movie is almost non-stop action, and where there is a momentary lull in the action, there is high tension.

In the film, prisoners at the breaking point due to poor conditions, overpower their guards and seize one of the blocks – or corridors – of cells.

Leading the revolt are two of the toughest actors ever in the movies: Neville Brand as the brains, and Leo Gordon as the muscle backing him up. Gordon who was in many movies and television shows, had actually served time in prison, and, from what I have read, could scare the crap out of almost anyone on any production. Brand, who was often cast as a thug in the 1940s and 1950s in films like "D.O.A.," here gets to play a tough guy with brains and a sense of justice.

The prisoners hold the guards hostage and issue a set of demands to the governor. The demands include more space in the overcrowded facility; removal of the criminally insane to a separate cell block; and separation of young offenders with light sentences from the hardened lifers.

Understanding the issues of the prisoners of Cell Block 11, the warden, played by Emile Meyer, is well aware of the problems, but can do little about them. Policy is set by state legislators and they and the governor refuse to spend any money to correct the conditions. Caught in a difficult situation, the warden must maintain order, contain the riot, and negotiate with the prisoners while dealing with a hard-nosed flunky sent by the governor, played by Frank Faylen. Faylen, here in a serious role, was a comic actor who played Dobie Gillis’ father on TV. Emile Meyer, often cast as tough ruthless characters, like the corrupt cop in “The Sweet Smell of Success” and the vice principal of the high school in “Blackboard Jungle,” gets a complex part to play here and does an excellent job.

“Riot in Cell Block 11” is not only a terrific action movie, it addresses realistic problems. And, as far as I could see, there is not a bad scene or a wasted frame of film in the entire movie.

Don Siegel did a great job on this, one of his earlier projects as a director. He later made five films with Clint Eastwood, including “Dirty Harry,” and “Escape from Alcatraz,” and he was a mentor to Eastwood in the actor’s early efforts as a director.

(For more posts on film and TV, check out Todd Mason’s blog.)

Monday, January 9, 2017

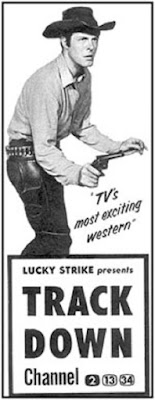

Trump Comes to Town on TV’s Trackdown

Last Saturday morning, cable’s ME TV channel showed an old, black-and-white episode of a Western series in which a man named Trump arrives in a small town and warns the people that meteors are about to hit and destroy everyone, and only he can save them.

He convinces the crowd and they clamor to buy his expensive protection – little umbrellas with symbols he claims have the power to deflect the killer space rocks.

Into this comes a Texas Ranger who tries to expose the fraud. But the people, carried away with fear, are willing to do anything to save themselves.

The episode, “The End of the World,” was from a show called Trackdown, and originally aired in 1958. The series starred Robert Culp and ran from 1957 to 1959.

(For more overlooked TV and film, visit Todd Mason’s blog.)

He convinces the crowd and they clamor to buy his expensive protection – little umbrellas with symbols he claims have the power to deflect the killer space rocks.

Into this comes a Texas Ranger who tries to expose the fraud. But the people, carried away with fear, are willing to do anything to save themselves.

The episode, “The End of the World,” was from a show called Trackdown, and originally aired in 1958. The series starred Robert Culp and ran from 1957 to 1959.

(For more overlooked TV and film, visit Todd Mason’s blog.)

Labels:

Robert Culp,

The End of the World,

Trackdown,

Trump

Friday, January 6, 2017

FFB: New Year’s Eve/1929 by James T. Farrell

This review was intended for last week’s Friday’s Forgotten Books, but the night before, a light snow storm knocked out the power in my area. Funny, the electric stays on through heavy rains and high winds, but let one snowflake land on a wire and a lot of little houses go dark. The lights eventually came back on, but the deadline had passed. So, here is what I hoped you all could have read before the calendar change.

James T. Farrell’s slim novel from 1967, New Year’s Eve/1929, takes place in Chicago on the afternoon, evening, night and the following morning of the last day of the 1920s and the first day of the 1930s. It is his bitter look back at the end of the Roaring 20s.

In the book, Beatrice Burns, a woman about 29 years old, dying of a lung ailment, possibly tuberculosis, lives near, and desperately wants to be part of, a group called the Fifty-seventh Street Art Colony. The colony was an actual group of writers, painters and college students residing in a south-side neighborhood near the University of Chicago. This is the same part of the city in which Farrell (1904-1979) grew up, went to college and wrote about in many of his novels, including his Studs Lonigan trilogy.

Beatrice longs for a blow-out New Year’s Eve party, a party to end all parties. A couple she knows, who usually throw huge parties seem too tired and uninterested in hosting anything that night. But Beatrice goes around telling people that there will be a big bash at the couple’s place, and feels she is doing everyone a favor by promoting a party.

That evening, the couple’s little apartment is jammed with people. Most know each other, everyone is talking at once, no one is listening much, and all are trying too hard to have fun. These people seem to know they are headed for tough times. This could be Farrell’s 20/20 hindsight, writing from a nearly 40-year distance.

One of the characters who appears in several of Farrell’s books, a writer named Dan O’Neil, comes to the party with a pretty young girl from the neighborhood whose mother does not approve of O’Neil. When Dan and the girl see Beatrice, they worry that Beatrice will cause trouble by telling the girl’s mother. Beatrice delights in knowing that she is upsetting them.

Dull and manipulative, Beatrice wants more than anything to be the center of attention. The idea of gaining the spotlight by causing trouble for others, thrills her. She takes note of couples sneaking off to the bedroom or locking themselves in the bathroom. She relishes the idea of catching them and having some juicy gossip. In short, Beatrice is a thoroughly dislikable character and a person the group barely tolerates and mostly ignores.

When a man gets drunk and starts shadow boxing, he accidentally clips Beatrice, knocking her to the floor. When she gets up, Beatrice laughs it off hoping the incident will finally draw everyone’s attention to her. It does, but momentarily.

At dawn, she tags along with a small group leaving the party. When they play a noisy game on the sidewalk, an irate neighbor throws cold water down on them. The water only hits Beatrice, and again, she laughs it off, hoping it will make her the life of the party. Instead, the group takes it as a sign the night – and the fun – is over and they go their separate ways.

New Year’s Eve/1929 is a quick, interesting read, but not a pleasant one. Anyone unfamiliar with Farrell would do better reading Young Lonigan (1932), The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan (1934), and Judgment Day (1935).

(For more posts on books, please visit Patti Abbott’s blog.)

James T. Farrell’s slim novel from 1967, New Year’s Eve/1929, takes place in Chicago on the afternoon, evening, night and the following morning of the last day of the 1920s and the first day of the 1930s. It is his bitter look back at the end of the Roaring 20s.

In the book, Beatrice Burns, a woman about 29 years old, dying of a lung ailment, possibly tuberculosis, lives near, and desperately wants to be part of, a group called the Fifty-seventh Street Art Colony. The colony was an actual group of writers, painters and college students residing in a south-side neighborhood near the University of Chicago. This is the same part of the city in which Farrell (1904-1979) grew up, went to college and wrote about in many of his novels, including his Studs Lonigan trilogy.

Beatrice longs for a blow-out New Year’s Eve party, a party to end all parties. A couple she knows, who usually throw huge parties seem too tired and uninterested in hosting anything that night. But Beatrice goes around telling people that there will be a big bash at the couple’s place, and feels she is doing everyone a favor by promoting a party.

That evening, the couple’s little apartment is jammed with people. Most know each other, everyone is talking at once, no one is listening much, and all are trying too hard to have fun. These people seem to know they are headed for tough times. This could be Farrell’s 20/20 hindsight, writing from a nearly 40-year distance.

One of the characters who appears in several of Farrell’s books, a writer named Dan O’Neil, comes to the party with a pretty young girl from the neighborhood whose mother does not approve of O’Neil. When Dan and the girl see Beatrice, they worry that Beatrice will cause trouble by telling the girl’s mother. Beatrice delights in knowing that she is upsetting them.

Dull and manipulative, Beatrice wants more than anything to be the center of attention. The idea of gaining the spotlight by causing trouble for others, thrills her. She takes note of couples sneaking off to the bedroom or locking themselves in the bathroom. She relishes the idea of catching them and having some juicy gossip. In short, Beatrice is a thoroughly dislikable character and a person the group barely tolerates and mostly ignores.

When a man gets drunk and starts shadow boxing, he accidentally clips Beatrice, knocking her to the floor. When she gets up, Beatrice laughs it off hoping the incident will finally draw everyone’s attention to her. It does, but momentarily.

At dawn, she tags along with a small group leaving the party. When they play a noisy game on the sidewalk, an irate neighbor throws cold water down on them. The water only hits Beatrice, and again, she laughs it off, hoping it will make her the life of the party. Instead, the group takes it as a sign the night – and the fun – is over and they go their separate ways.

New Year’s Eve/1929 is a quick, interesting read, but not a pleasant one. Anyone unfamiliar with Farrell would do better reading Young Lonigan (1932), The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan (1934), and Judgment Day (1935).

(For more posts on books, please visit Patti Abbott’s blog.)

Labels:

Chicago,

James T. Farrell,

New Year’s Eve/1929,

Studs Lonigan

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)