Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Jack’s Return Home (aka Get Carter) by Ted Lewis

If you’ve heard that Ted Lewis’ Jack’s Return Home is one of the grittiest British crime novels ever written – believe it.

Is Jack’s... the original British noir? No. Others got there first, including Gerald Kersh’s 1938 Night and the City.

But are any of the other stories tougher than Lewis’ 1970 book? Put it this way, it would be quite a feat to outdo Jack Carter – an enforcer for two London gangsters – for coolness, street smarts, and violence.

Jack must have rocked many a cozy little English village when it hit the bookshelves.

The story opens with Jack Carter returning to his home town, an industrial city in the north of England, after learning his brother Frank died in a car accident. Jack goes up there to bury Frank and to make sure his teenage niece is all right.

The circumstances of the car crash are fishy. Frank was murdered and Jack sets out to learn why and who did it. This takes him through the seamiest places in the city and to some stately places built by local gangsters – men who Jack knows well from the old days.

Jack, the first-person narrator of the story, is an uneducated poet. He tells his tale in a combination of slangy dialogue and impressionistic images of the cold, wet town.

“The misty rain was dense enough to practically obscure the neighboring blocks. Only dull lights separating soft at the edges were evidence of the other flats,” he says while looking for someone in a public housing project.

A horrible scene is coolly described by Jack when goes to see Albert, a once cocky, small-time hood. Albert is now a broken-down hulk living in a dilapidated house next to a steel mill. A disheveled old lady answers the door. The place smells. A sloppy woman sits on a folding lawn chair near two filthy children. The former tough guy – now only about 40 – is rooted in a chair, drinking. All are watching a crummy TV set. A door to a bedroom opens. A man comes out buttoning his clothes. A woman comes out tying a bathrobe and Albert introduces her as his wife.

Jack’s energy is almost superhuman as he moves around the town getting into multiple fights, putting the clues together and taking his revenge on the men who killed his brother.

Jack’s Return Home was later reissued as Get Carter, the title of the excellent 1972 Michael Caine movie based on the book.

Ted Lewis (1940-1982) grew up in northern England, went to art school, worked in advertising and in animation – including the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” – and wrote nine novels before dying at age 42.

Friday, October 28, 2022

Two truly scary films for Halloween

Halloween is approaching, and while there are more than enough slasher films and boogeyman movies to watch this weekend, here are two films that should scare the stuffing out of any viewer.

Free Solo

Mountain climber Alex Honnold goes about his sport without a helmet, without spiked books, without ropes, and without other climbers. He free climbs using just some chalk on his fingers and a pair of sneakers on his feet. In this 2018 documentary, Honnold attempts to climb the sheer rock wall of El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park.

The Alpinist

Marc-Andre Leclerc also likes to climb alone. While he does bring equipment with him, his special thrill is climbing in winter on the ice that forms on mountains. This 2021 documentary follows him as he travels looking for greater challenges.

Both of these films have photography that is unbelievable – beautiful, breathtaking – and action to make palms sweat. So chalk up and check them out.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

Roseanna by Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall

Reading Roseanna confirms that Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall were a hell of a great crime writing team.

Their publishers must have thought so, too. The pair went on to write nine more police procedurals featuring their fictional detective Martin Beck of the Swedish national police.

The story opens when workers repairing a set of locks connecting two lakes in Sweden’s inland waterway dredge up the naked body of a young woman.

Local police find no one in their small city who can identify the murdered woman. The investigation widens and Martin Beck is brought into the case.

Beck and his team figure the woman was a passenger on a cruise ship passing through the locks. The woman must have been killed on the boat and then dumped overboard.

The detectives determine which boat she was aboard and set about finding the the crew and other passengers. It is a long, painstaking process. Wahloo and Sjowall take their time yet make the police work fascinating.

Detective Martin Beck is an odd sort of hero. He is good at his job, but rather morose, always seems to have a cold, complains about the weather, and has no rapport with his wife and kids. He only connects with the guys he works with and even then he is a bit chilly.

Wahloo and Sjowall keep the story and its many clues and suspects clear and orderly. The authors had a clean, no nonsense writing style and the Lois Roth translation is well done.

Per Wahloo (1926-1975) and Maj Sjowall (1935-2020) were not only writing partners but also partners in life.

Thursday, September 29, 2022

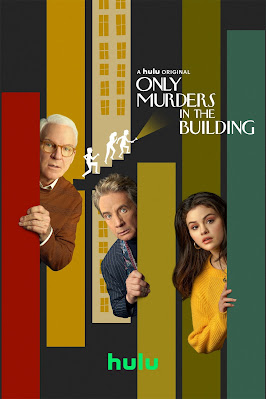

Only Murders in the Building is a series to watch

In this comic mystery series, three residents of an old, stately Manhattan apartment building meet and then learn that another resident died mysteriously. The three, played by Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Selena Gomez, knew the young man by sight and are sure he must have been murdered. They decide to not only investigate on their own, but also create a day-by-day podcast of their activities.

Martin

plays a semi-retired actor who once starred in a popular TV crime

series and thinks he can apply methods from the show to the real murder.

Short plays a washed up Broadway theater director who sees the

investigation as a way back into the limelight. And Gomez, who was house

sitting for a wealthy aunt, has a mysterious connection to the murdered

man.

This series, streaming on Hulu, plays out like a well done

comic novel – think, A Confederacy of Dunces. And, by the way, why

hasn’t Confederacy ever been made into a film or series?

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

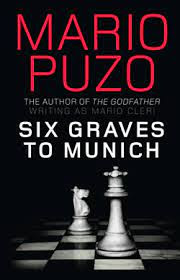

Six Graves to Munich by Mario Puzo

In 1969, author Mario Puzo hit the jackpot with his blockbuster novel, The Godfather, about the fictional Corleone crime family.

For many years before that, he made a living writing stories for men’s magazines. Then in 1967 he published the novel, Six Graves to Munich, under the pen name Mario Cleri.

Six Graves to Munich is a short (224-page), fast-paced thriller set in Europe during

the Cold War era. It is tale of vengeance, full of sex and violence.

During World War II, Michael Rogan, was a U.S. intelligence officer

married to a French woman. He and his wife were captured by the Nazi’s

and tortured. His wife died.

Ten years later, after a long recovery, Rogan returns to Europe to find the men responsible – and kill them.

One of the torturers Rogan hunts was Italian army officer. He tracks

the man down to Palermo, and learns he is a high ranking mafioso and

well protected.

In this section of the book, Puzo’s knowledge

of the underworld is evident. It reads like a test run for the sections

of his next book in which Michael Corleone hides out in the hills of

Sicily. But, in keeping with Puzo’s men’s mag background, Rogan, while

on the trail of the man he wants to kill, takes time out for a steamy romp with a

beautiful young Italian woman.

Today, with 20-20 hindsight,

Six Graves to Munich, with its suspense and period detail, might be

taken as Puzo’s warm up for his big novel.

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

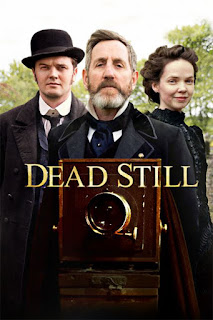

Dead Still is a series to watch

One of the weirdest mystery shows to come along has to be Dead Still.

The six-part series is about a Victorian photographer who specializes in memorial shots – or pictures of dead people made to look like they are still alive.

How some of these dead people got to be that way and why dumps the photographer into a world even stranger than the one he made for himself.

The show was shot in Ireland with a terrific cast, including the superb Michael Smiley as the photographer.

Check out the trailer here.

Thursday, June 30, 2022

Two Shots of Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest, and an earlier series called, “The Cleansing of Poisonville,” published in the pulp magazine Black Mask, are the same story.

Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest, and an earlier series called, “The Cleansing of Poisonville,” published in the pulp magazine Black Mask, are the same story. Both tell how the Continental Op – Hammett’s unnamed operative for the fictional Continental Detective Agency – comes to a small Western city called Personville (nicknamed “Poisonville”) to help rid it of gangsters, crooked cops and corrupt politicians.

In Poisonville, the young publisher of the city’s local paper is waging a campaign to clean up the town. The publisher’s father owns the paper, the mine, and several other prominent businesses. The father also has the leading citizens and top officials in his pocket. But the father is old and losing his grip. Racketeers have moved in and divided up the city.

Unwilling to side with any one group the Op sets about turning the gangs against one another so they will destroy themselves.

It is a complicated story filled with violence and double crosses.

The four Black Mask stories – “The Cleansing of Poisonville” (November 1927); “Crime Wanted – Male or Female” (December 1927); “Dynamite” (January 1928); and “The 19th Murder” (February 1928) – are included in their original form in The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) compiled by Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett.

When the stories appeared in Black Mask, they caught the attention of a book editor who approached Hammett with the idea of publishing them as a novel. But first the editor wanted Hammett to make some changes. He suggested cutting some of the violence to make the story more believable, according to Layman and Rivett.

The book, called Red Harvest after Hammett submitted a page of alternate titles, was published in February, 1929, by Alfred A. Knopf.

Reading the stories and the book at the same time shows interesting changes made by Hammett in his transition from pulp writer to novelist.

Key cuts were the dynamiting of police headquarters and the bomb killing of one of the three gang leaders. The Op’s escape over the rooftops from an ambush was also cut. And the shootout at the Silver Arrow Club was streamlined and in the book.

There are small changes on almost every page of the novel. Often they are as simple as a word choice or a rewritten sentence. Most of these changes tightened the writing, eliminating repetitions in dialogue, but they also took away some of the flavor.

Hammett was always good at creating realistic dialogue. In his pulp stories, he used a good deal of the underworld slang of his era. The amount of slang was reduced in the book, or altered to clarify a point. The book editor may have felt that readers of the novel would be less familiar with the slang than the readers of Black Mask.

The changes made the writing a little less colorful and took some of the rough edge off the tale, but did not damage the storytelling. Hammett was still Hammett, and the tough, lean writing style was still there. Even Hammett’s earliest stories showed this talent.

For the slang that remained, Layman and Rivett, the editors of The Big Book..., found some of the words and phrases needed footnotes for current readers to understand them.

Future readers of Hammett may need even more annotations. The time may come when a Hammett story will require as many footnotes as a Shakespeare play.

But with our without the explanations, Hammett’s work is always a pleasure to read.

Tuesday, May 3, 2022

The French Connection Revisited

Many people are familiar with the case from the 1971 Oscar-winning movie, “The French Connection.” Fewer may know the case from Robin Moore’s 1969, non-fiction book.

Moore detailed the painstaking and sometimes hair-raising work of detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso leading to the seizure of more than 100 pounds of heroin and the arrest of some – but not all – of the drug traffickers.

Egan

and Grosso got on to the case by chance. After working round the clock

for several days, they went to a night club for a drink. There they

spotted a young guy being treated like royalty by some known wiseguys.

Wondering what was up, the detectives followed the guy who turned out to

be the nephew of a mob boss. The guy seemed to have some suspicious

connections of his own. By night he made pickups and deliveries around

town. By day, he and his young wife ran a lunch counter and candy store

in Brooklyn.

For weeks, Egan and Grosso watched the man. Keeping

an eye on the luncheonette, the detectives observed some shady

characters coming and going. The detectives got warrants to tap the

man’s home and business phones. When the wiretaps picked up some foreign

voices, Egan and Grosso were on to the French connection.

They

identified a key player, but tailing the Frenchmen proved to be harder

than expected. At one point, the man gave Egan the slip in the subway

and waved at the detective as the train left the station. The filmmakers

used that moment in the movie.

But the book and the movie differ.

The

movie – which is one of the great crime films – invented some scenes

not in the book, like the car chasing the train. The book had scenes in

cars that may have been too confusing to film, as when the Brooklyn man

routinely drove up and down Manhattan streets to shake any possible

police tail and making it hard for the detectives to follow him. At one

point, Grosso, dressed as a delivery boy, tried to follow on a bicycle.

They found that a 1960 Buick Invicta had panels under the car that when taken off revealed spaces perfect for hiding contraband. They arranged for the car, which had been brought in from France, to be left on a particular street. The mob guys would then move the car into a rented garage on that block, open the panels, take out the packages of heroin, replace the panels and put the car back on the street to be picked up by their French contacts. They even had a jar of mud from France to smear on the panels. If the police tested the dirt, it would look like nothing had been done to the car since it left Europe.

Moore’s book ranks up there with the best non-fiction crime stories, and, like Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, it reads like a novel.

Robin Moore (1925-2008) wrote about 60 books, often with co-authors, including other true crime stories and The Happy Hooker. He died at age 82 while working on three new books. Moore served in the Air Force during World War II, then went to Harvard. In the early 1960s, he approached one of his college acquaintances, Robert F. Kennedy, and gained access to the Army Special Forces. In 1965 he published The Green Berets.

Tuesday, April 5, 2022

New York Dead by Stuart Woods

Stuart Woods introduced his calm, cool, rich lawyer, Stone Barrington in his 1991 novel, New York Dead.

When this novel opens, Stone is not yet rich or a lawyer, but he is cool. Cool enough to eat at Elaine’s, a Manhattan restaurant frequented by celebrities.

Stone is a 15-year veteran of the New York Police Department and one of its detectives. While on medical leave after taking a bullet in the knee, he witnesses a woman fall from a 12-story building, landing on a hill of dirt in a neighboring construction site. Miraculously, the woman lives. An ambulance is called.

Did she jump? Did she fall? Was she pushed? The latter seems the best scenario when Stone pursues someone fleeing the woman’s building. His bad knee keeps him from making an arrest.

Although he is supposed to be home recovering, he convinces his superior to let him take the case, along with his partner, Dino Bacchetti.

As if surviving a fall from a high building is not enough of a twist, when Stone and Dino check on the woman’s condition they learn she disappeared from the ambulance taking her to the hospital. Complicating matters, the woman is a well-known TV news anchor.

The police brass, anxious to close this case and get it off the front pages and the evening news, railroad a suspect Stone believes innocent. Going head to head with his superiors gets Stone bounced off the force on the pretext that his knee will never recover well enough for him to resume his duties.

But Stone – one of the luckiest characters in mystery fiction – runs into an old pal, an attorney at a prestigious law firm. The firm could use someone with Stone’s experience. And just like that, Stone is drawing a big salary while continuing his own investigation of the woman who fell.

What may be surprising to readers of the later Stone Barrington books is how much Stone and Dino clash in this first novel. It is not until the end that they seem to form a real friendship. Dino will continue being a prominent character in the later Barrington books.

To date, Stuart Woods has published 61Stone Barrington novels. They are fast, enjoyable reads. His first novel, Chiefs, from 1981, is a rural mystery spanning several generations in a Southern town. It won an Edgar Award.

Thursday, March 17, 2022

Dark Crime Novel, The Informer, by Liam O’Flaherty

Forget everything you might remember about the movie, “The Informer.” The book it was based on will knock you on your arse with its realism, squalor, crime, and violence.

In Liam O’Flaherty’s 1925 novel of the same name, Gypo Nolan is not the lovable oaf played by Victor McLaglen in John Ford’s 1935 film. He is a beast roaming the slums of Dublin. O’Flaherty almost always describes the powerful giant with the slow brain in animal terms, except when comparing him to plants or rocks.

Gypo Nolan is about as down and out as a person could get in the Ireland of the early 1920s. While the country was struggling to establish a new, independent government, political factions and splinter groups were fighting among themselves, inflation was on the rise and the poor were getting poorer. The only money Gypo could lay his his hands on was from beating and robbing sailors or through handouts from Katie Fox, an emaciated, drug addicted, prostitute.

Once a police officer, Gypo was thrown off the force. He then got involved with a Communist organization looking to dominate the new government and in need of a thug. Sent to deal with a farm labor group, Gypo and his old pal Frank McPhillip got drunk and Frank shot and killed one of the farm leaders. This got both of them thrown out of the radical group. Frank, with a price on his head, was forced to hide in the countryside. Gypo returned to the slums of Dublin.

Living in a men’s shelter, Gypo is surprised to see Frank sneak in and tell him he is ill, possibly dying, and is going home to visit his parents.

This puts an idea in Gypo's head. Tired of being broke, wanting a good meal and drinking money, he decides to go to the police, tell them where to find Frank, and claim the £20 reward (about £1,200 pounds or $1,500 in today’s money, but could have been a lot more due to the conditions of the time).

In a skirmish with the cops, Frank is killed.

Now, with the money in his pocket, Gypo goes right into a bar and starts drinking. The bartender is stunned when Gypo produces a pound note to pay. For a guy everyone knows is on the skids, pulling out a bill worth about $70 or more would be stunning. Katie Fox comes in, sees Gypo has money and starts cadging drinks off him and manipulating him to give her some cash.

Carried away with his new prestige as a man of means, in one of the best scenes in the book, Gypo goes into a little fish and chips shop and buys food for anyone who wants to eat. He spends recklessly and a big crowd gathers. Among them is a member of the radical group of which Gypo was once a member.

The group and its leader, Dan Gallagher, now suspicious of Gypo and his new found wealth, haul him into a secret tribunal and get the truth out of him. He was the one who informed on Frank. Every member of the group is now in peril if Gypo ever goes to the cops again. Gypo is sentenced to die, but he escapes, runs through the streets like a frightened animal and is finally killed by the group. Before he dies, he stumbles into a church where Frank’s mother is praying and he asks her forgiveness.

Unlike the sentimental movie, the ending of the book is graphic and unsettling.

Another person in the story who emerges as a main character is Dan Gallagher, the young leader of the revolutionary group. Gallagher is a man committed to the Communist movement, but reveals to Frank’s sister, a young woman in love with him, that his – Gallagher’s – ideas and goals are not fully formed or even well thought out. He enjoys the power of leading men, but is confused about many things.

Frank’s sister, Mary, is the only character who has a chance of escaping the slums and the wretched lives of the people around her. She finished school and got an office job in a Dublin company. If only there had been a little more about her, the book would not have been so bleak. But a dark, bleak tale is what O’Flaherty set off to tell and it is what he achieved.

Liam O’Flaherty (1896-1984) was born in the rural Aran Islands, studied to be a priest for a while, fought in the English army in World War I, had Communist leanings, wrote 14 novels and many short stories and has been considered one of Ireland’s great, if overlooked authors.

The Informer is a marvelous read, even if O’Flaherty, describing the squalor and poverty, lays it on a little thick. At times he also sails off on wordy tangents, waxing poetic and nearly forgetting the point he was trying to make. But those passages are few and do not take away from the power of the book and of O’Flaherty’s ability to describe the inner workings of Gypo's mind.

Before leaving the impression that the novel is a grim slog, there are some funny moments in The Informer, as when Gypo beats up a man in the street and then beats up the cop who came to break up the fight, then searches for the tiny little hat he always wears:

“His massive round skull stood bare under the night. It stood naked, hummocked and gashed here and there, like a badly shorn sheep. He traversed the skull with his right palm, in little flurried rushes, as if he had had a vague suspicion that the hat was hiding somewhere along the expanse of skull.”

It is a brutal humor, but then, brutal is a good word for the book.

Monday, February 21, 2022

First Principles by Thomas E. Ricks

Here is something different for today, away from the mean streets of mystery and crime.

It is Presidents’ Day, which seemed like a good day for a few words about my favorite book of 2021: First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned From the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country by Thomas E. Ricks.

Ricks, a career journalist now retired from the Washington Post, was interested in learning just how America’s founding fathers figured out how to create a democratic government and what a republic would look like. He knew the stories of the men and the battles they had with each other in hammering out the rules that would guide the new country. But how did those men know where to look for guidance?

To find out, Ricks selected four of the founders to concentrate on: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and James Madison. He looked into their backgrounds, focusing on their education, where they went to school, the subjects they studied, and what those schools were like in the 18th century. Ricks even found and profiled some of their instructors.

Higher education in those days meant reading the classics. Even Washington, who did not have as extensive a formal education as the other three, was familiar enough with the classics for Ricks to trace the general’s tactics in fighting the British to passages from ancient Rome.

First Principles is a fascinating book, and unlike a lot of histories, it is written in a sharp, accessible style, something that could be expected from a man who spent his life writing about complex issues for newspaper readers.

As a final thought, it may not be remembered, but not so long ago, our politicians could refer to the classics. In a 1968 speech, Robert F. Kennedy reflecting on the death and destruction of the war in Vietnam, said:

“I am concerned that at the end of it all ... they may say, as Tacitus said of Rome, ‘They made a desert, and called it peace.’”

Monday, February 7, 2022

Framed in Guilt by Day Keene

Robert Stanton, former World War II pilot and later a prisoner of war, now a best-selling novelist with an enormous salary from a movie studio, receives a call from a woman just arrived from England who tries to blackmail him. She has proof that during the war, Stanton married a London girl then abandoned her and her child.

Stanton meets her, kills her, and leaves a trail of clues. The body is discovered early the next day. Police arrive and Stanton, suffering after a heavy night of drinking, claims he never heard of the dead woman. He cannot account for himself at the time the murder and he cannot explain the clues that brought the police to his door.

How the crime was committed is not too tough to figure out, but who actually did the killing is well concealed until the exciting end of the story.

Day Keene was having some fun, taking pot shots at the typical Hollywood types. There is the beautiful, self-centered starlet, and the handsome, self-centered leading man, the sniveling producer married to the daughter of the studio chief, the boorish gossip columnist, and the snappy, fast-talking newspaper reporter trying to nail Stanton and get a scoop. And then there are the detectives of the Los Angeles Police Department who routinely take suspects into a back room of a precinct and beat confessions out of them.

Stanton’s sidekick is an Oxford educated, Native American who speaks like an English barrister, but also enjoys acting the part of the powerful and stoic Indian.

A bit of dialogue that may be unintentionally funny occurred when a leading man complains that Stanton purposely gives supporting players the best lines, Stanton fires back:

“Oh, so I let my personal feelings enter into my writing?”

God forbid any personal feelings enter into the making of a Hollywood movie – back then or today.

Keene freely switches points of view between characters whenever he needs a convenient way to hide a fact or an identity.

Overall, Framed in Guilt is a decent whodunit, a breezy read, and a fun peek behind the scenes of Hollywood in its Golden Age.

Information on Day Keene is sketchy and inconsistent. Most say he wrote more than 50 novels, as well as short stories and scripts for radio and television. Some say he was born in Chicago in 1903, others claim 1904. All agree he died in 1969, although I could not find an obituary for him. Sources all agree that “Day Keene” was his pseudonym, but there is some confusion about his actual name, which was either Gunard Hjertstedt or Gunnar Hjerstedt. Anyone who can lend some clarity to this is welcome to comment.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Walking the Perfect Square by Reed Farrel Coleman

In his 2001 novel, Walking the Perfect Square, Reed Farrel Coleman introduced Moe Prager.

Prager, a former officer with the New York Police Department who was forced into retirement after a serious knee injury, now at loose ends. He is not sure what he will do next. His older brother, Aaron, wants him to be his partner and open a family-run wine shop in Manhattan. Prager would not mind being a silent partner in the store, but he cannot see himself in that business.

Then Rico, his partner when he was on the force, calls and says someone could use his help. Francis Maloney, an offensive middle-aged suburban bigot with powerful friends in New York politics and the police department, wants Prager to find his son, Patrick.

A college student, Patrick was last seen at a private party in a Manhattan bar. Witnesses said one minute he was there, the next he was gone. No one saw him go and no one knows where he might have gone. He did not return to his Long Island school, and he did not go home to his parents. Friends looked for him, the police looked for him, his family looked for him, and even though many were still trying to find him, no one had a clue.

After a meeting filled with insults, Prager is not interested in helping the father with anything. But Francis Maloney, through Rico, knows Prager and his brother want their own wine store. Maloney, with his connections, can make their state application sail through the bureaucratic process. Maloney also knows the story of when Prager was a cop he found a missing child and rescued her. Maloney wants Moe Prager’s skill and luck in finding his son.

Prager accepts the job and things get weird quickly.

Patrick, the missing student, was a strange young man, according to guys in his dorm. One of them witnessed, through a partially open door, Patrick walking backwards making a perfect square over and over again. A couple of girlfriends said Patrick was desperate and could be violent.

Moe Prager, who had wanted to be an NYPD detective, uses both his police skills and his personal charm and intelligence, to find people and get them to open up and tell him things they either hid from other investigators or just remembered after talking to him.

As Prager gets closer and closer to finding the missing student, he begins to suspect he is being used by someone or some group for reasons other than finding the kid. Some clues, contacts, and information were just too easy. The mystery of Patrick’s disappearance becomes almost secondary to the mystery of who was out to get who, with Moe Prager in the dangerous middle.

Reed Farrel Coleman is a terrific writer and one of my favorites among current crime novelists. Walking the Perfect Square has a unique structure, starting in 1998 – the recent past for a 2001 book – the story jumps back to 1978, where most of the sleuthing takes place. At times, the story shifts back to 1998 to tease the reader, then dives back into 1978 again. At the end of the initial mystery, Coleman jumps forward to 1998 to wrap up the many mysteries woven into this piece.

Coleman knows the territory and Moe Prager’s first person narration makes the city and the people come alive. There is also a good deal of self-deprecating humor, as when he muses about the stupid accident that caused his knee injury, he quips, “That’s me, Moe Prager, nobody’s hero.” When Moe has to go into a tough, dive bar, he checks that his gun is handy, feeling like Gary Cooper in “High Noon,” only to find, “When I walked in even the flies yawned.”

Most of the time, Coleman’s writing style has the hard feel of a Lawrence Block novel or a Robert B. Parker book.

For a review of Reed Farrel Coleman’s third Moe Prager mystery, The James Deans, click here.

Monday, January 10, 2022

Dress Her in Indigo by John D. MacDonald

More than 50 years after its publication, John D. MacDonald’s 1969 mystery, Dress Her in Indigo, provides a look back at the hippie era, a time that scared the crap out of parents of teenagers.

In this 11th book in the Travis McGee series, the daughter of a wealthy older man leaves college and goes to Mexico with a group of friends and dies in a car accident near Oaxaca.

The man asks McGee and his pal, Meyer, to leave South Florida and go there to find out what the girl was doing, what her life was like, and if she was happy.

(I don’t recall if McGee, the first person narrator, ever calls Meyer anything other than Meyer, or lets the reader know Meyer’s first name.)

McGee and Meyer hop a flight and get to work seeking out young Americans, asking about the girl, picking up her trail and learning about her “friends.”

Author MacDonald was about 52 or 53 when he wrote Dress Her in Indigo, so he, and his 40-ish protagonist, McGee, were the older generation observing the younger. While he tried to give the hippies the benefit of the doubt by painting some of them as lost and confused, or industrious artists doing their own thing, there was a distinct smell of disapproval coming off the pages.

Not that all bohemian types repelled McGee. At one point he hooks up with a slinky, rich European woman who lives for sex, and nearly kills him with her requirements in the sack. Meyer, too, finds some free love with a very young Mexican woman.

Soon, McGee uncovers disturbing facts about the dead girl’s car accident and starts digging into the case.

The mystery is less interesting than MacDonald’s portrait of the self appointed leader of the girl’s group, an intense, charismatic con man.

Was art imitating life here? Did MacDonald write the book after the Tate–LaBianca murders of August 1969. Or was MacDonald predicting this type of character emerging?

%20(1).jpg)

%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)

2.png)